Eternalist Generationalism

(Note to Reader: What follows is a refracted, more “grown-up” version of what I’ve been circling around for a while.

Call it a foundational essay on Eternalist Generationalism—what I mean by it, why it matters for fathers, and what it actually demands of us in real time, not just in theory.)

1. Two ways of living in time

I keep coming back to one basic fork in the road.

Either:

This life is all you get. You flare into existence for a few decades, then vanish. No judgment, no eternity, no God taking any of it seriously.

Or:

You and I are creatures made for eternity. Our souls endure. Our choices echo beyond the grave. History isn’t just random motion; it’s a story with a Author and an end.

Those are not “vibes.” They are mutually exclusive accounts of what time is.

If #1 is true, then the honest play is fairly simple:

Minimize suffering, maximize pleasure and comfort, keep your options open, and hope your kids do okay. Any talk of sacrifice, vows, duty to the unborn—all of that is just marketing or personal preference.

But if #2 is true—if there is eternity—then almost nothing is trivial.

My habits, my loyalties, my worship, the way I spend my hours as a father…they are not just “my story.” They are stitches in a fabric that runs forward into generations—and upward into judgment.

Most of our culture lives as if #1 were true while still recycling bits of #2’s language—“legacy,” “values,” “making a difference”—as brand copy. That schizophrenia is part of why so many men feel insane.

Eternalist Generationalism is my attempt to pick a side and live it all the way down.

2. The lie of individual optimization

Modern culture tells me my primary job is to “optimize” myself and my kids:

optimize our health

optimize our education

optimize our finances

optimize our opportunities

Get the right sports, right schools, right supplements, right neighborhood, right devices, right career ladder.

But somewhere beneath that check-list, a harder reality has been bothering me:

My children cannot thrive long-term in a diseased civilization.

I can feed them grass-fed beef, read them great books, homeschool with the best curriculum in the world…but if the habitat around them is hostile—spiritually, culturally, legally—then their odds of flourishing (and their children’s odds) drop fast once I’m no longer there to hold back the tide.

If eternity is real, and my line matters, then this “optimization” mindset is radically too small. It focuses on the organism and ignores the ecosystem.

At some point I had to admit:

It’s not enough to raise “good kids” in a bad world.

I am responsible, to some degree, for the world they will inherit—not in some abstract global sense, but in the concrete places where my family actually lives: our parish, our town, our land, our laws, our community.

From there, the question changes:

Not just “How do I raise decent kids?” but

“How do I, as a finite father, cooperate with God in shaping a habitat where my descendants can remain human, faithful, and free when I’m long gone?”

That’s the generational piece.

3. The machine vs the covenant

There’s a system—call it “the machine”—that thrives on short-term thinking and isolated individuals.

The machine:

trains us to be isolated (no real neighbors, only online “followers”)

keeps us infertile or low-fertility (kids as lifestyle accessories, not covenantal duty)

keeps us overworked and over-entertained (too tired to think, too distracted to revolt)

makes everything rentable and nothing inheritable: homes, tools, skills, even our children’s minds and bodies.

It offers its own answer to the eternity question:

“There is no eternity. But we can simulate a kind of fake immortality for you through data, comfort, brand, and distraction. Your job is to feed the machine and enjoy the ride.”

Against that, I’m proposing something intentionally stubborn and unfashionable:

A life that assumes eternity is real, that sees the family as a covenant across generations, and that understands land, parish, law, and local economy as part of that covenant’s conditions.

That’s what I call Eternalist Generationalism.

4. What I mean by “Eternalist Generationalism”

This is not a full system yet. It’s early. I’m still sanding edges, throwing pieces out, adding better ones. But here’s my working definition:

Eternalist Generationalism is a way of seeing and living as a father that treats eternity as real, time as a gift, the family as a multi-generational covenant, and local culture/land/law as a habitat we are morally bound to shape for our descendants’ souls.

To make that less slippery, here are some core theses I’m trying to live by and write from:

Eternity is real, and judgment is real. My first duty is to God: to love, worship, and obey Him as revealed in Christ and taught by His Church. Everything else sits under that.

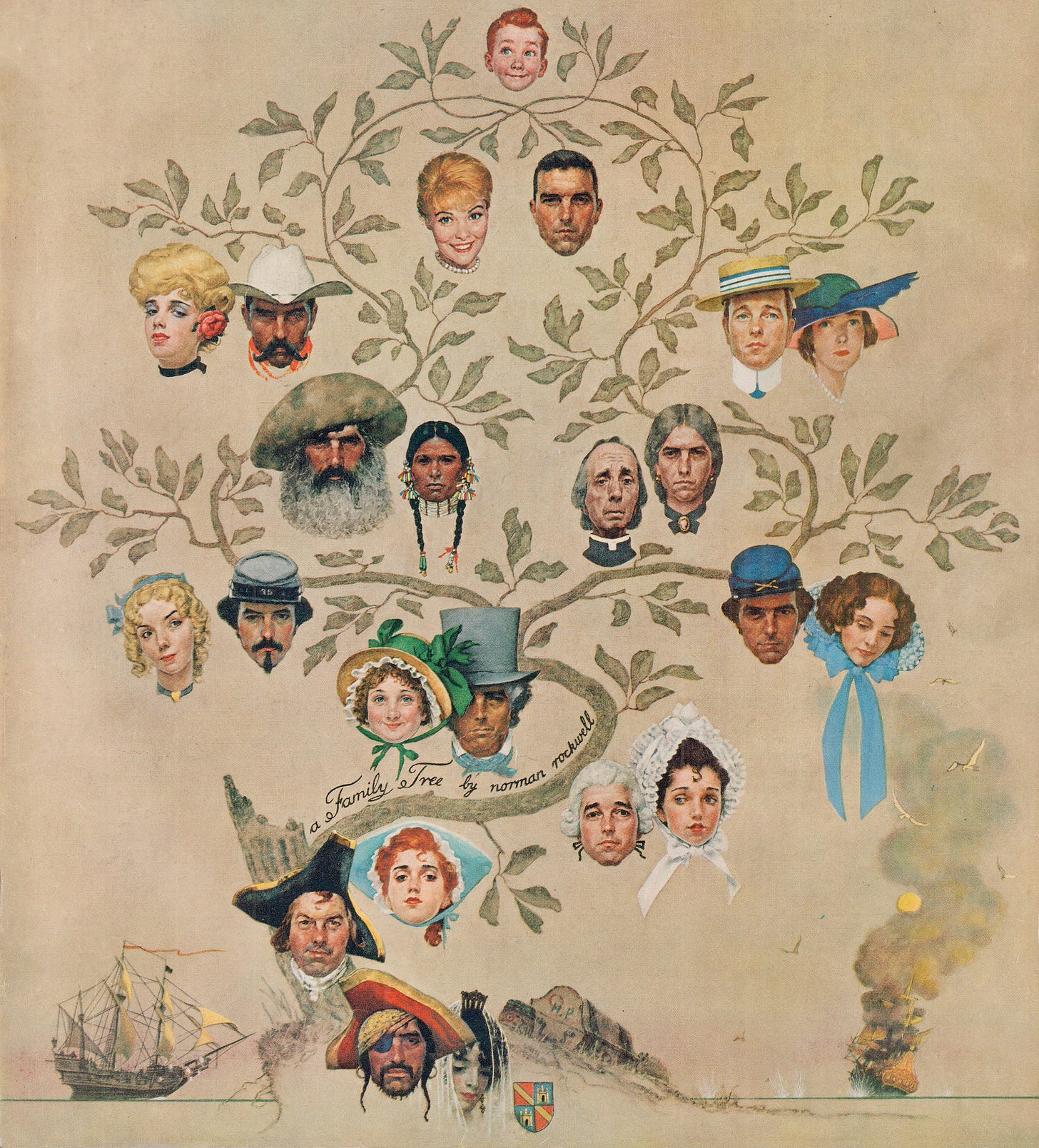

My family is a covenant, not a lifestyle. Marriage and children are not aesthetic choices. They are a binding, multi-generational partnership between me, my wife, our ancestors, our descendants, and God.

I owe a debt to both the dead and the unborn. I inherit gifts (faith, land, language, traditions) I didn’t earn. I’m morally bound to preserve, deepen, and pass them on—not strip-mine them for personal use.

Habitat matters as much as heroics. My kids don’t just need me to be a “strong dad”; they need a sane ecosystem: parish, neighbors, laws, land, economy. I’m responsible, with others, for shaping that ecosystem.

The machine is real and must be resisted. Large-scale systems—educational, medical, financial, digital—tend to flatten persons and families into units of consumption and compliance. My job is to withdraw where necessary, subvert where possible, and build parallel structures when I can.

Human scale is the right scale. Whenever possible, I should prefer what is small, local, and personal over what is large, remote, and abstract—households over corporations, parishes over vague “global Christianity,” towns over empires, tools that serve families over systems that own them.

Repentance is built into the blueprint. Because I am a sinner and my descendants will be sinners, Eternalist Generationalism must include confession, forgiveness, and course-correction as normal moves—not embarrassing exceptions.

Those are not branding bullet points. They’re the skeleton.

Everything I build—Dissident Dad as a call to other men, Kinward as a set of concrete alternatives, our homestead and eventual farm, the way we school our kids—has to hang on those bones or it’s just noise.

5. The ends: what is this actually for?

If I’m not careful, this whole thing can drift into:

“We’re going to build a perfect little life for ourselves,” or

“We’re going to save America,” or

“We’re going to be the last sane people on earth.”

None of those is the real end.

The true end, if I take my own eternalism seriously, is:

To cooperate with God in the salvation and sanctification of my soul, my wife’s soul, my children’s souls, and as many neighbors as I can, within the concrete conditions He has placed me—using time, land, culture, and institutions as material for love.

That means a few hard distinctions:

Heaven is the ultimate homeland, not any country. I can be “America first” in the order of earthly duties—wanting my country healed, wanting my kids to inherit something real here—while still remembering that the City of God is not stamped with any flag.

The common good is more than my family’s comfort. I don’t get to build a fortress and forget the town. A truly ordered love of my wife and kids spills outward into parish, neighbors, and even enemies. If my “generationalism” becomes a bunker, I’ve missed it.

Economics, politics, and culture are servants, not gods. Farming, homeschooling, running a café, starting a coffee company—these are means. If they ever become ends in themselves, I’ve simply built a prettier machine.

6. Institutions, not just vibes

It’s easy to talk about “culture” and “community” in a vague way. The thinkers I’ve been immersed in push me beyond that.

If I want my line to endure in any meaningful sense, then I need more than a private code of honor. I need institutions that outlast me:

A parish worth belonging to.

A place where the sacraments are real, doctrine is taught, feasts and fasts are kept, and my children are known by name.A household with a rule of life.

Daily prayer. Meals together. Real work. Sabbath. Systems for confession and forgiveness. Clear expectations for boys and girls as future men and women, not permanent adolescents.Local economic structures.

Family businesses, cooperatives, trade relationships, mutual aid—things that keep us from total dependence on distant corporations who hate us and our kids.Educational alternatives.

Homeschool co-ops, micro-schools, apprenticeships—anything that forms our children in truth and competence without handing their souls to bureaucrats.Shared rhythms.

Feast days. Seasonal gatherings. Sunday dinners. Work parties. Actual traditions that give shape to the year and tie families together.

Eternalist Generationalism, if it’s real, has to show up there. Otherwise it’s just a clever label slapped on the same scattered, isolated pattern of life everyone else is living.

7. Tech, media, and the paradox I’m stuck in

I’m not naïve: I’m writing this on a screen, publishing it through platforms that are part of the very machine I’m critiquing.

That paradox matters. If I ignore it, I become just another “content creator” selling a mood.

So here’s my working stance:

I use digital tools as signposts and summons, not as a place to live.

The point of every post, essay, or podcast is to nudge men off the screen and into:

the chapel

the field

the workshop

the dinner table

the town hall

In our home, that means explicit tech boundaries. In my writing, it means I have to keep asking:

“Is this post helping men step into reality, or just giving them a little dopamine hit of agreement?”

Eternalist Generationalism can’t just be a brand aesthetic on a feed. It has to have a built-in bias toward reality: bodies, places, voices, sacraments.

8. Sin, failure, and antifragile families

One of the dangers of talking about “eternal impact” and “generations” is that it can sound like I have any of this under control.

I don’t.

I am a sinner, married to a sinner, raising little sinners in a world that’s very good at discipling them away from God. We will:

fight

say things we regret

misjudge situations

over-protect in one area and under-protect in another

blow decisions about money, discipline, community

Eternalist Generationalism cannot be a perfectionist fantasy. It has to assume we will fall—and build repentance and repair into the structure.

That means:

We confess. To God, to each other, to our kids.

We forgive, and ask to be forgiven.

We course-correct in public, not just in private shame.

We design our little institutions (household, businesses, communities) so that when—not if—they are stressed, they don’t shatter; they learn.

In modern terms: we want our families and parishes to be antifragile—to grow stronger through trial, not collapse at the first hit.

That’s not romantic. It’s costly. It requires humility, which is not my default setting. But if we’re talking about eternity and generations, there is no alternative.

9. So what does this actually call a man to do?

If you’re a dad reading this, wondering what any of this means on Tuesday morning, here’s the short version.

Eternalist Generationalism, embodied, looks like:

Ordering your loves.

God first. Then wife. Then children. Then extended family and local people. Career and online identity slide down the ladder.Rooting yourself somewhere on purpose.

Not just chasing cheap housing or status, but choosing a place where faith, family, and community can actually breathe—and then staying long enough to matter.Taking the sacraments and worship seriously.

No more treating Mass or church like a box to tick. This is the axis of your week, the place where eternity touches time and your kids watch you kneel.Reclaiming your household as a small civilization.

Meals. Stories. Chores. Catechism. Work. Rest. Hospitality. Your home is not a hotel with screens; it’s a training ground for saints and citizens.Building or joining parallel structures.

Homeschool co-ops, local businesses, neighborhood groups, parish men’s circles—imperfect, humble, but real. Get your hands dirty. Don’t wait for a perfect community; help build one.Accepting that you won’t finish the work.

You’ll start things your children or grandchildren will finish—or abandon. You plant trees you may never sit under. Your job is to be faithful to your piece of the story.

10. Closing the loop

I’m writing all of this as a man in the middle of it, not above it.

I’m trying to build a homestead and (eventually) a farm. I’m fumbling my way through being a husband and father who loves Christ and His Church. I’m starting Kinward as a set of real-world experiments: coffee, café, community, land.

And I’m writing as Dissident Dad because I’m tired of pretending any of this is normal. It’s not. The default settings for men in our time lead to loneliness, divorce, addiction, and children who inherit nothing but debt and digital ghosts.

Eternalist Generationalism is my attempt to name a different path:

Faithful to Christ.

Loyal to wife and children.

Bound to ancestors and descendants.

Suspicious of the machine.

Committed to actual places and people.

Honest about sin and failure.

Stubbornly hopeful.

Is it finished? No.

But I’m convinced it’s worth a life’s work to hammer it into clearer shape—

to live it out in dirt and sweat and liturgy—

and to share it with other men who feel the same split in their chest and refuse to hand that feeling over to a therapist or a brand.

If eternity is real, then your fatherhood is not a side quest.

It is one of the main ways God is stitching His story through time.

The only question is whether we’ll show up for our part.

Kinward: From Philosophy to a Way of Life

If Dissident Dad is where we name the problem and recover the language of eternalist generationalism, Kinward is where we build the answer.

Kinward is not a content brand or lifestyle aesthetic. It is the long project of turning this philosophy into concrete forms of life—homes, parishes, farms, businesses, brotherhoods, and local networks ordered toward God, rooted family, and multi-generational durability.

If this framework lands for you—if you feel the obligation to build something your great-grandchildren can inherit rather than escape—then Kinward is the banner under which that work gathers.

Join us → joinKinward.com

(Movement updates, gatherings, practical tools.)